Google’s Flu Analytics Fail Highlights Big Data’s Shortcomings

Big data has enormous potential for assisting public health efforts, but without sufficient context, numbers can be misleading. An attempt to track flu outbreaks around the world based on Google search data has not lived up to expectations, according to a recent policy paper published March 14 in the journal Science.

|

|

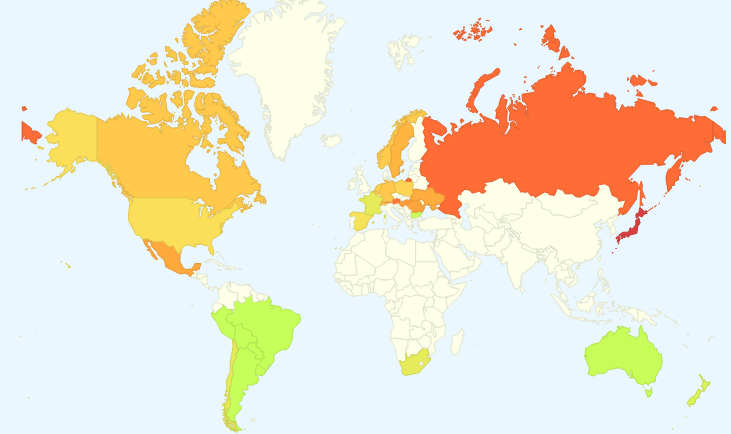

| Google Flu Trends heat map for Friday, March 14. | |

“The Parable of Google Flu: Traps in Big Data Analysis” – authored by David Lazer, a computer and political scientist at Northeastern University in Boston, and colleagues Ryan Kennedy, a University of Houston political science professor, Alex Vespignani of Northeastern University and Gary King with Harvard University – examines where Google’s data-aggregating tool, called Google Flu Trend (GFT), went wrong. The research calls attention to the problematic use of big data from aggregators such as Google.

“There’s a huge amount of potential there, but there’s also a lot of potential to make mistakes,” Lazer told Live Science.

With input from Google’s search engine that matched terms for flu-related activity, the flu tracker was launched in 2008 to provide real-time monitoring of flu cases around the world. According to a recent Nature article the tool initially performed very well, with researchers in many countries having confirmed that its influenza-like illness (ILI) estimates are accurate. However, a series of glitches tell a different story.

According to the Science article, GFT has persistently overestimated flu prevalence, leading health and policy experts to rethink the algorithmic approach to disease surveillance.

From August 2011 to September 2013, the Google-developed tool over-predicted the prevalence of the flu in 100 out of 108 weeks. For the 2012-2013 and 2011-2012 seasons, it overestimated flu prevalence by more than 50 percent. And during the peak flu season last winter, the Google tracker indicated twice as many flu cases as the number of actual reports collected by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The problem extends back to 2009, when Google Flu Trends missed spotting the non-seasonal H1N1-A flu pandemic.

The Science report’s authors write: “Even 3-week-old CDC data do a better job of projecting current flu prevalence than GFT.”

Although Google has not commented on the matter, it does recalibrate its models to adapt to changes in the viruses and in people’s search behavior. While some experts are betting the algorithm will “bounce back” after these refinements are implemented, others argue that the problem extends deeper than that.

Determining exactly where Google Flu Trends went off the rails is not easy because the company’s search algorithms and data-collection processes are proprietary. Still the authors of the Science paper contend that the problem is fixable. They recommend an approach that combines big data with small data, i.e., traditional controlled datasets, to create a deeper and more accurate representation of human behavior.

The other important caveat is to consider the origin of the data. Both private companies and social networking outlets may intentionally or unintentionally manipulate data to ensure product relevancy or ad revenue.

“Our analysis of Google Flu demonstrates that the best results come from combining information and techniques from both sources,” notes Kennedy. “Instead of talking about a ‘big data revolution,’ we should be discussing an ‘all data revolution,’ where new technologies and techniques allow us to do more and better analysis of all kinds.”