Schools Get a Leg Up on Terrorists with Big Data

Governments around the world spend billions of dollars each year trying to prevent terrorist attacks, with varying degree of success. When preventative efforts fail, the next best option is to help potential victims prepare by predicting when and where attacks are most likely to occur. That’s the approach a United States data analytics startup is taking with schools half a world away in Pakistan.

More than 20 years after establishing a foothold in the mountainous region of the Afghanistan-Pakistan border, the Taliban is still a force to be reckoned with. That’s particularly evident when it comes to educating children, which the Islamic extremist group fervently opposes. Over the past five years, there have been more than 10,000 attacks on Pakistani schools, including the destruction of 1,000 of those schools. Most of the attacks were conducted by the Taliban, which killed 132 schoolchildren in the December 2014 massacre at the Army Public School in Peshawar. It is the deadliest attack in Pakistan’s history.

While we’re still a long way from seeing the Taliban driven from the region, it’s clear that authorities needed to do something to protect the children. So in March the United Nations announced plans to address the issue through the new Pakistan Safe Schools initiative. A key element of that initiative is the data and analytics technology that Raleigh, North Carolina-based PredictifyMe will bring to bear on the problem.

Raleigh is a long way from Peshawar. But PredictifyMe’s co-founder and chief data scientist, Zeeshan-ul-Hassan Usmani, grew up in Pakistan before pursuing graduate studies in the United States. As a Fulbright Scholar at the Florida Institute of Technology, Usmani did his PhD work on building simulations that modeled blast waves in open and confined spaces. His Master’s thesis, meanwhile, was on observing and quantifying the effects of “herd behavior” on shoppers in supermarkets.

Out Smarting Terrorists

Combining these seemingly unrelated disciplines—the physics of shock waves on the one hand and a model of human behavior on the other—gives Usmani the analytic foundation on which to make predictions concerning the timing and results of terrorist attacks.

As part of the partnership, PredicifyMe will work with the United Nations to use its software to analyze the potential for terrorist attacks at 1,000 Pakistani schools. If the results are successful, it will be widened to support more schools around the country.

There are two main products at play here. The first product, called Soothsayer, predicts the likelihood of a terrorist attacks, and covers the human behavior aspects of terrorism. The software works by using its machine learning algorithms to analyze the signals generated by about 200 different indicators, such as the weather, the day of the week, the presence of sporting events or major holidays, the existence of attacks in nearby countries, visits by foreign dignitaries, or blasphemous videos posted on social media. According to Usmani, Soothsayer can predict terrorist attacks with 72 percent accuracy within a three day window.

The second product, SecureSim, has more to do with modeling the physics of blast waves generated by terrorists wearing suicide vests. Given the size of the bomb (as measured in air pressure per square inch), the software is 92 percent accurate in determining how many people in a building will die and what kinds of injuries the survivors will sustain. That information can not only inform schools about the best way to place entrances, but it can tell emergency personnel what kinds of surgeries will need to be performed to have the best chance at saving lives.

It may sound grisly, but Usmani has dedicated a large part of his professional career to evaluating this type of information. In 2006, Usmani founded the website Pakistani Body Count, which keeps track of causalities in the country. So far, the website has tabulated the deaths of nearly 6,500 people due to suicide bombings and nearly 3,500 due to drone strikes.

The data has yielded common patterns in both suicide attacks and drone attacks. Pakistanis are five times more likely to die in a drone attack if walking in a tribal area during the weekend than a Monday morning, Usmani said in a 2010 article in The Express Tribute. Almost 90 percent of the attacks happen between 2 a.m. and 8 a.m.

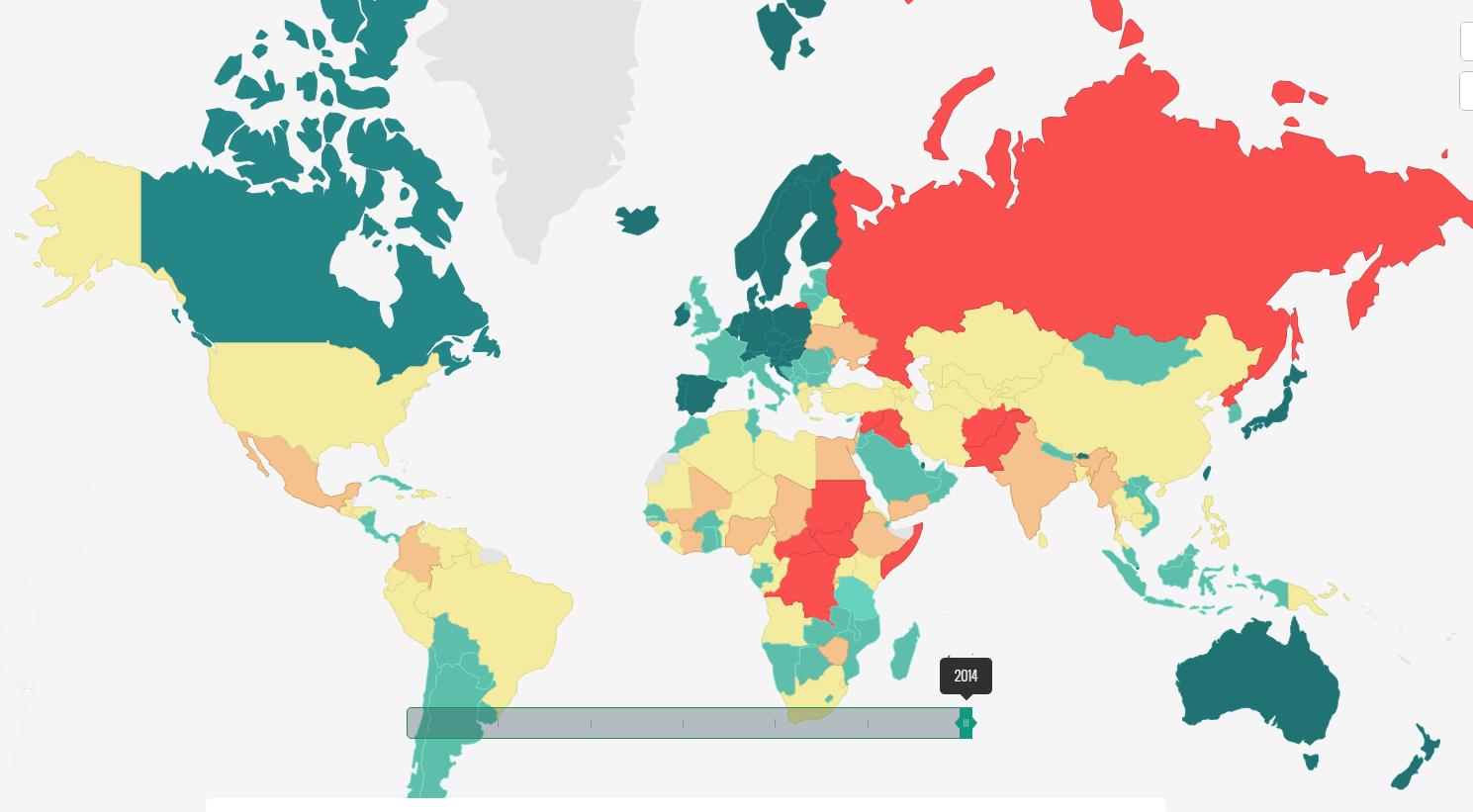

Terrorists may be outliers on the spectrum of human behavior, but they still behave in predictable ways, Usmani says. For example, data shows that terrorists may be more inclined to launch an attack in retaliation to videos, books, or cartoons that Muslims find offensive. In Pakistan, PredictifyMe will use a variety of indexes, such as the Global Peace Index, to gauge the relative levels of unrest that may be occurring in any given country at any given time.

It’s no use trying to beat the algorithms to stay under the radar. “Once you try to become unpredictable, that becomes a pattern by itself,” Usmani tells Datanami.

Leveraging Massive Open Data

PredictifyMe the is doing the work in Pakistan pro bono. But it’s gearing up to launch a series of shrink-wrapped predictive analytic products, dubbed “Hourglass,” that will drive profits here in the States. The software, due out later this year, will make use of predictive analytics to help companies in the healthcare, insurance, and retail fields make better business decisions.

The idea is to use combine client’s internal data with public data that’s freely available to build predictive models based on what customers or prospects are likely to do. With 137,000 data sets available from Data.gov alone, there is huge potential to build predictive behavioral models and then put them to use.

And the data is just going to get bigger. According to Usmani, there are a half a million data sets available measuring 100,000 variables in human behavior. People in the United States are throwing off the most data of all. “Our estimate is that Americans were generating 1 TB per person per year over the last 10 years,” he says. “Over the next 10 years, they’ll be generating 20 TB per year per person.”

“There is far more data available and it’s increasing every single day in a way that would surprise most people,” says PredictifyMe co-founder and CEO Rob Burns.” The U.S. is unique in the amount of data that they’re making available…However you can still look at human behavior in the United States and adapt it for other countries around the world.”

There is an underlying theme in PredictifyMe’s work that says people from vastly different parts of the world still behave in predictable ways. Before he puts on a suicide vest, a would-be terrorist follows a predictable pattern in his daily life.

“What often surprises people is that there are distinct patterns,” Burns says. “I agree that there are occasions when people’s behavior is completely unpredictable. But I think that percentage is far, far smaller than the average public would realize.”

Related Items:

GPU-Powered Terrorist Hunter Eyes Commercial Big Data Role

How Big Data Analytics Can Help Fight ISIS