Will the Fall of ‘Society’s Genome’ Trigger the Next Dark Age?

(Nejron Photo/Shutterstock)

Over the past 20 years, we’ve witnessed a remarkable transformation of our society, and digital information is at the very heart of it. But what if we were to suddenly lose all this data that we’ve amassed, or a big chunk of it? It would be, quite simply, devastating to Western civilization, argues the CEO of Spectra Logic in a new book.

In the new book, titled “Society’s Genome: Genetic Diversity’s Role in Digital Preservation,” Spectra Logic CEO Nathan Thompson takes a fascinating look at the intersection of data with our daily lives.

Take a look around you, Thompson says, and you’ll notice that there’s hardly an element of society that humans haven’t digitized and automated in some fashion or another. “We’re dependent on data,” Thompson says. “Communication, medicine, social services, natural defense, trade, transportation, production of basic commodities, food production – everything has become dependent on this enormous amount of digital information that society has created.”

Data is nothing new to humans, of course, but our relationship to data has changed dramatically. Fifty thousand years ago, early humans recorded data on the walls of caves, and oral histories were passed down from generation to generation. But our ability to preserve data increased dramatically with the creation of papyrus scrolls.

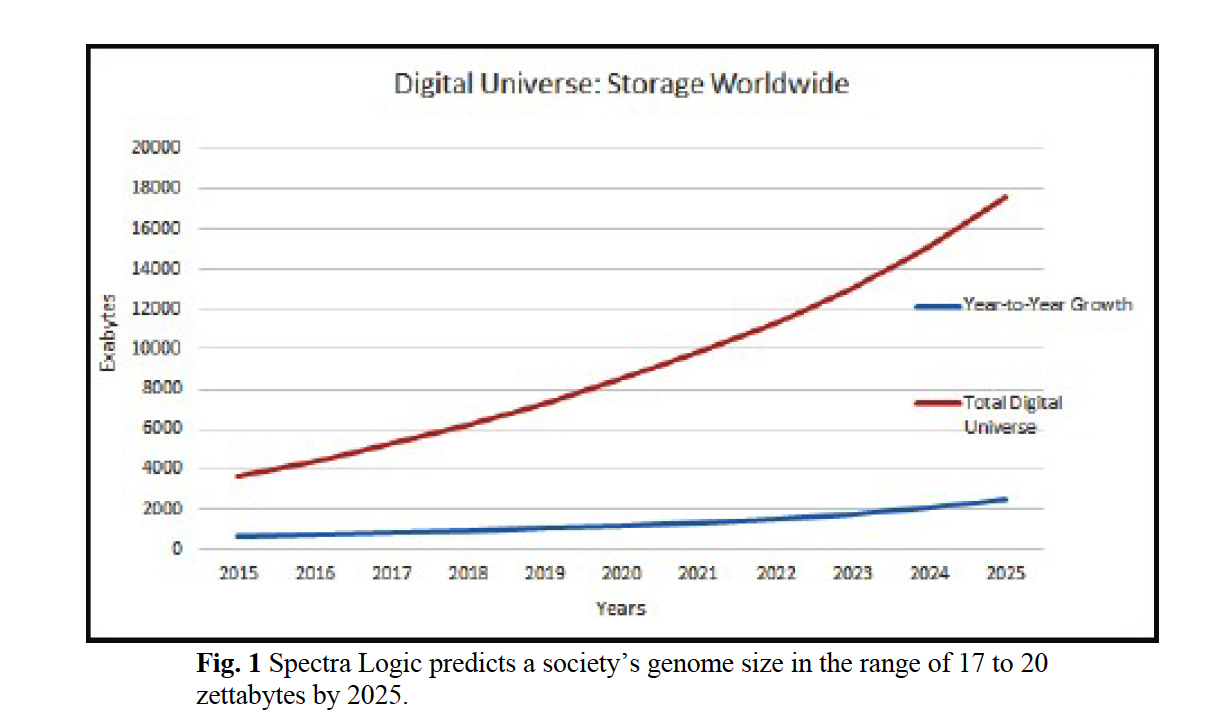

While analog storage of data on paper is still in widespread use today, we’ve clearly moved toward digital storage techniques. We wouldn’t be in a “big data” boom without efficient ways to store massive amounts of information. But that concentration of information into a handful of storage big data carries existential risks. Thompson argues that we’re not as aware of those risks as we should be.

“Ten years ago, we could probably go backward in the event most digital information was lost,” Thompson tells Datanami. “But at this point, there is no going back. If for some reason we lost a large part of the digital universe…we could almost end up in the Dark Ages again as humanity because we’re so darned dependent on it.”

Past as Prologue

This has all happened before, of course.

After the long decline of the Roman Empire in about the sixth century A.D, the continent of Europe descended into an 800-year funk known as the Dark Ages. Scientific progress stopped, fear and superstition reigned, and Europe didn’t get its groove back until the beginning of the Renaissance in the 14th century.

Ptolemy’s map (image source: Wikimedia Commons)

Human knowledge took a significant hit during that time, including the apparent loss of maps created by Claudius Ptolemy, a Greco-Egyptian writer, astronomer, and cartographer who lived in the first and second century A.D. The maps in Ptolemy’s book “Geographia” were so accurate that they are deemed to have facilitated the expansion of the Roman Empire, as well as global trade.

When Geographia was lost – possibly in one of the fires that destroyed the great libraries in Alexandria – so was the data they contained. “When a set of copies were found in Constantinople, which is now Istanbul, in 1295, the scholars went through the maps and the data points, and concluded that he had a better map of the world….than anything that had been created in the last 300 to 500 years,” Thompson says.

Other examples of mass data loss include the loss of the Bakhshali Manuscript, an Indian work of mathematics written in Sanskrit that was “a collection of computational, arithmetical, and algebraic algorithms and simple problems.” The manuscript was written on birch bark, perhaps around the same time Ptolemy assembled his master work. (And let’s not forget the Irish monks who “saved civilization” by copying and translating many of the books in the Alexandria library that otherwise would have been lost forever.)

If a large chunk of our modern data was lost, it would be catastrophic to Western civilization, Thompson argues. The population would shrink by a factor of 100, if not more, due to food production, medical care, and trade being so dependent on data. “Life as we know it would end,” he says. “And those who survived, which would be very few, would go back to something you might see in the Amazon with a tribe that hasn’t really been in contact with Western Society.”

Preventing Data Armageddon

Thompson offers a few strategies for preventing data loss that could spur the meltdown of society. In particular, Thompson and his co-authors, Bob Cone and John Kranz, take their cues from nature, which has developed very sophisticated ways of protecting data.

“The solution we came to is, just as organisms have sets of chromosomes and genes, organizations do too, and so does all of society,” Thompson says. “The term ‘society’s genome’ comes from looking at the set of data. This is what will move us forward as a society.”

Humans must become even more adept at utilizing data in the future if the world is going to be home to a projected 10 billion people by 2030, Thompson says. “We’re going to have to use more and more data and information-intensive strategies to feed and clothe and house that base,” he says.

We would be smart to emulate nature’s techniques for safeguarding genetic material, Thompson says. The biggest take-home, from a practical standpoint, means diversifying the number and types of storage mediums that we use.

“It’s not about backup or archive,” Thompson says. “It’s about applying nature’s toolkit, which is making multiple copies, trying to deploy genetic diversity, so it’s not just stored in one kind of method.”

While we may or may not be using DNA-based storage (Thompson says it’s a possibility 50 years down the line), we can help to boost our chances of retaining our data heritage for generations to come by being aware of the risks.

Spectra Logic CEO Nathan Thompson

“The message is pay attention to the methodologies that have served us well in the past,” Thompson says. “If you look at some of the factors that caused destruction of data, in the past it has been program error and user error. At the present time, there’s a significant risk of outsiders effecting information, like the ransomware threats.”

Being too heavily dependent on spinning disk drives also raises the risk. Thompson mentions what happened at Saudi Aramco, “where somebody planted a virus in 30,000 disk drives and wiped out 30,000 disk drives,” he says.

Diversify Your Storage

While no media is infallible, spinning disk drives deserve special consideration.

“A disk drive will have between 5 million and 7 million lines of code in it, written on five continents,” Thompson says. “No one person understands what all that code does. A defect or a bug or a bomb planted in a disk drive, and every disk drive of one manufacturer will wake up and stop working at some point. There are systemic risks if we’re not careful.”

(source: Society’s Genome)

Thompson encourages diversity of storage, and preaches against homogeneity. For example, tape drives–which continue to store massive amounts of data despite being declared dead as a technology countless times–can be part of an effective storage mix. Cloud-based storage, and even optical technologies, all play a part.

Just as the USDA has multiple seed vaults to protect the genetic data contained in seed crops, individuals and organizations should take pains to ensure their data is safe by practicing heterogeneity in data storage.

“The only thing that rely saves you is making multiple copies, separating them, and having a method of verification” that they’re accurate, such as check-summing or taking hashes, Thompson says. “Ideally you’re making copies on something other than on the same media type. Any one media type can be subject to a particular failure or attack.”

You can read more about “Society’s Genome” at www.societysgenome.com/. You can buy an electronic copy for your Kindle or other e-reader on Amazon. Paper-based backups are also available.

Related Items:

The Growing Menace of Data Hoarding

Cutting On Random Digital Mutations and Peak Hadoop

Dangers in Data Definition – How Data Quality Can Save Lives