How Do You Value Information?

(enzozo/Shutterstock)

If you’re like most people, you recognize that information has value. The value isn’t always clear, but it’s clearly there. But according to some professional organizations, digital information literally has no value. As Gartner’s Doug Laney explains, the emerging field of Infonomics provides a starting point for getting answers.

It sounds inexplicable, but it’s true: Information has no official value in the eyes of the property and casualty (P&C) insurance industry. Nor does it have any official value to the accounting folk who set the Financial Accounting Standards (FAS).

This may sound like a bad joke or fluke of the law, but it wasn’t funny at all to the companies that were unfortunate enough to be based in the World Trade Center fifteen years ago.

Laney, a distinguished analyst covering big data and analytics at the storied Connecticut analyst firm, explains what happened to those firms in a compelling keynote yesterday at the Veritas Vision 2016 conference here in Las Vegas, Nevada.

“Some of the companies in the Twin Towers who lamented not only the tragic loss of life and physical property also lost their data,” Laney said. “So naturally what they did when they suffered some kind of loss was they reached out to insurance companies and they filed claims for the value of the information that they lost in the attacks.”

However, the insurance companies denied the claims, saying they didn’t believe that information constitutes property and therefore were not covered under P&C policies. What’s more, the insurance companies actually went so far as to update the commercial general liability (CBL) policy standard that’s used by most insurance companies around the world to explicitly exclude information from P&C polices.

“When did they do that?” Laney said. “A month after 9/11.”

Electronic Mass

That was a bit of an eye opener for Laney, who came up with the “3 Vs” definition of big data in 2001 while working at META Group, which Gartner acquired in 2005. “I had always thought of information as property,” he said. “I had always thought of information as a valid asset.”

Electrons have no measurable mass, therefore digitized data can’t be considered property, ruled one court (Rivan media/Shutterstock)

Laney decided to pursue the matter. If the insurance companies didn’t consider information property, and the accounting firms wouldn’t consider information an asset, then just what was information? Clearly, information is something.

He looked to the courts, but didn’t find much. “The courts are confused,” he said. “Some of the courts have said information can be represented by bubbles on an optical drive or it can be printed and so forth, so it should be considered property. Other courts have said ridiculous things like, well electrons have negligible mass so information shouldn’t be considered property.”

When Laney talked to clients, he heard executives speak glowingly about the value of information. “We often hear people talking about information as an asset,” he said. “CEOs often say things like ‘Information is one of our biggest resources and biggest corporate assets.’ They pay it a lot of lip service.”

Clearly, the CEOs of Fortune 500 aren’t deluding themselves into thinking that information is valuable. There is value there, even if you can’t measure it like you can a bank account, a fleet of trucks, or a building. That led Laney to explore how other types of assets are valued.

Asset Valuation

Laney found several definitions on how to value assets. It all boiled down to three things:

- An asset is a thing that can be owned and controlled; and

- An asset is something that’s exchangeable for cash; and

- An asset is something that generates probable future economic benefits.

Does information meet these requirements? Absolutely.

“I don’t think there’s any argument that information meets those three criteria,” Laney said. “We’re just in a world today where our accounting practices are antiquated and arcane, dating back actually to the Great Depression.” Besides a few tweaks that government economists made to the way that Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is calculated to account for data, there has been no progress made in information valuation in over 80 years.

(A related challenge has emerged in how to accurately measure productivity of workers in the digital economy. Those models haven’t kept up with technology, and as a result, economists report that the productivity of American workers is decreasing, which is clearly wrong.)

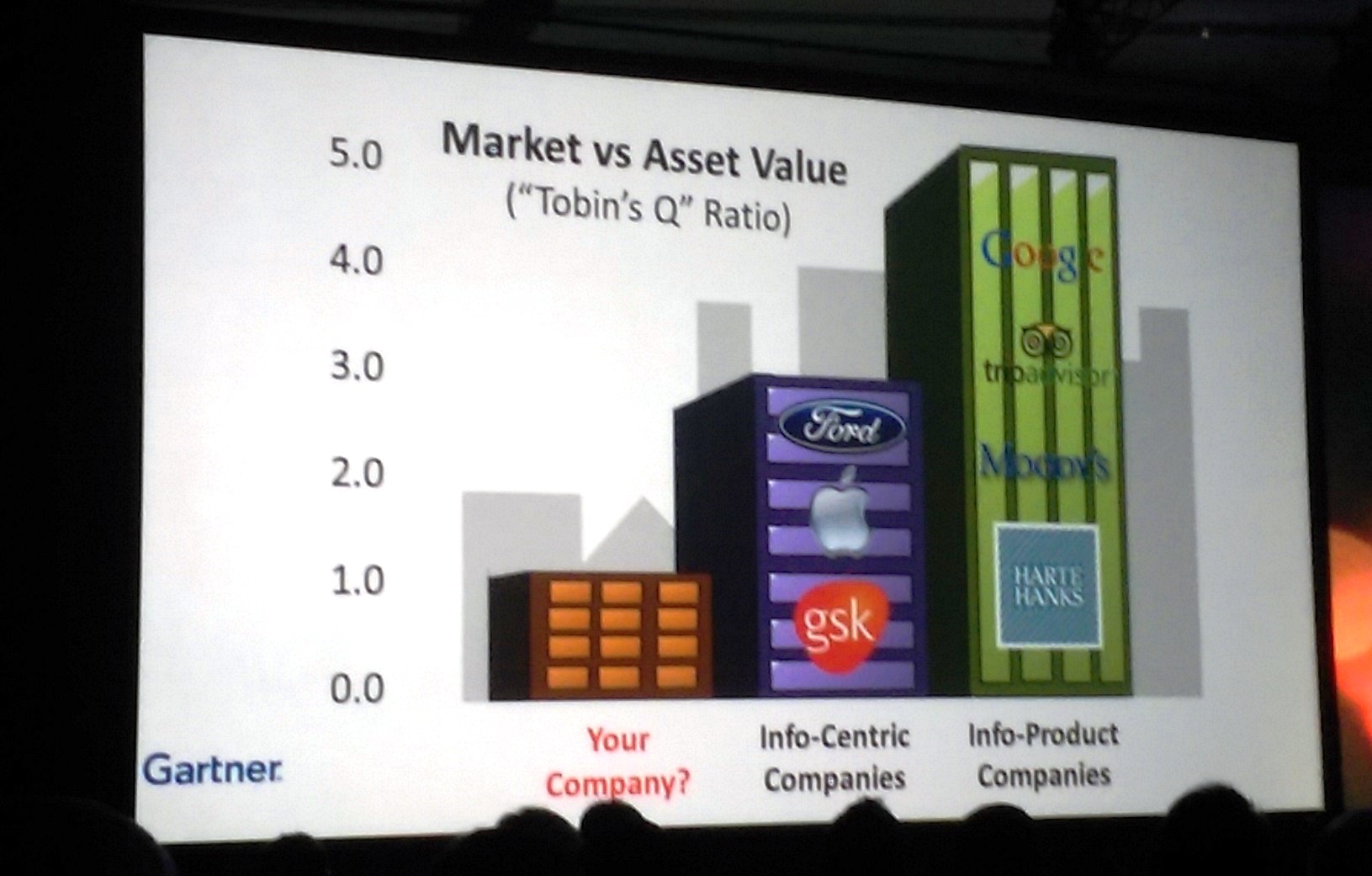

Wall Street rewards companies that are better at managing and monetizing information with higher valuations

Making some progress, Laney next decided to get empirical, and see how the smart money on Wall Street valued companies that were better at managing, manipulating, and monetizing data than their peers.

“We did some research a number of years ago. We looked at companies that were more information-centric. These are companies that have chief data officers, that have enterprise data governance [strategies], that have data science organizations, proving that they want to do more with their data, they want to govern it and manage it better as an actual asset,” he said.

“What we found is those kind of information-centric companies…have a market to book value…that’s two to three times higher than the norm. So while these companies may not look different from the outside, there’s something about the way they behave when it comes to information assets that investors tend to recognize.”

Rise of Infonomics

As his research continued, Laney and his colleagues came up with a name for what they were doing. They decided to call it Infonomics, with the core assumption that information should be considered an asset and treated accordingly.

“I don’t care too much what the accountants say,” Laney said. “I think it’s really incumbent upon organizations to behave as if information is an asset. What that means is that it should be managed with the same discipline as any other physical or financial asset, or human capital. You should be monetizing it with great fervor, and you should be measuring its potential, and also the actual value that you’re generating from it. Only then are you really able to maximize its value.”

There are three main aspects of information that Laney seeks to measure with Infonomics, including the realized value of information, the probable value of information, and the potential value of information. Laney says it’s not the value of the information itself, but rather the difference in value as measured by these indicators, that is important.

“There are gaps–large gaps in most organization–between the potential value and the realized value, or the realized value and the probable value,” Laney said. “Those things need to be measured, and those gaps need to be closed if you want to win in today’s information economy.”

Valuation Models

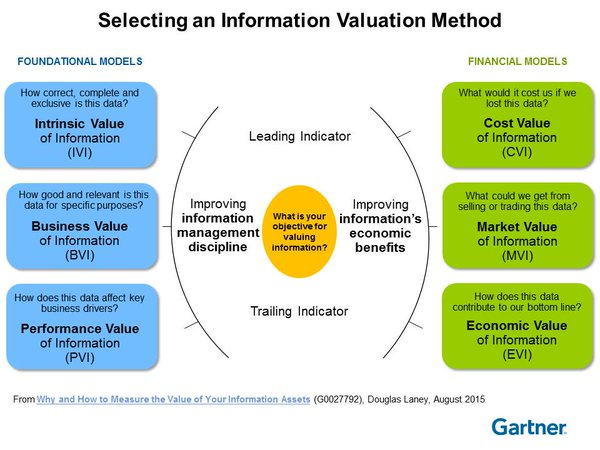

Laney and his Gartner colleagues analyzed how assets are valued in other industries, and came up with six models to measure the value of information at companies.

“These are classic ways that valuation experts value any type of asset,” he said. “What we’ve done is we’ve tuned them a bit, tweaked them for some of the nuances of information, like when you sell information, you’re really licensing it. When you consume information, it’s not depleted.”

Depending on the industry, a cost-based model might be best for measuring the value of information. However, other companies might benefit from the market value-based approach. Laney called the income-based approach, which measure the contribution to a top line revenue stream or top line number, the “Holy Grail” of information valuation.

“There’s a variety of ways you might want to measure information,” he said. “These are models we’ve published in Gartner research.”

These models aren’t just academic exercises, but have provided actual benefits to real-world combines. Gartner shares the story of an Indiana company that looked at what it was spending to manage and secure data, and the benefit it was actually getting out of it.

Gartner Distinguished Analyst Doug Laney

“What they found is that some of their information assets were costing them more to store and secure and so forth, than the value they were getting from them, so they made a defensible disposal decision and they’re now saving over $1 million.”

An alarm system company, meanwhile, discovered they were sitting on information that was underutilized. “Most companies innovate around processes,” Laney said. “What they did was they innovated around underperforming information. By doing so, they ended up adding $300 million in market value to the company by innovating around an underperforming information asset.”

An Emerging Discipline

Many companies today talk about becoming “information-driven,” or “data-driven.” (In this context, information resides a little higher up the totem pole of knowledge than raw data.) But to truly become information-driven, it’s worthwhile to know what the value of your information is, and to find ways to maximize that value. That’s the study of Infonomics.

Infonomics isn’t a household word, but it’s gaining traction among those who work with information, data and knowledge. Laney founded the Center for Infonomics in 2010, according to the infonomics entry in Wikipedia, and pretty soon you might be able to hire an infonomist to analyze your organization’s use of information; the University of Illinois plans to offer an MBA in Infonomics in the near future, Laney said.![]()

So what can you do to further the study of Infonomics in your organization? Laney encourages prospective information innovators to invite their CFOs into a conversation about how to value information.

“Go to your CFO and say, listen we understand information is not a balance sheet asset. No big deal,” he said. “But we’re in the middle of information economy. We think that we need to start measuring information value and potential within the company with the same discipline that you, Mr. or Mrs. CFO, measure our other assets, our traditional balance sheet assets. And the answer is invariably yes.”

When will information get formally recognized for actually having value? Laney isn’t holding his breath waiting for a group of accountants, insurers, and lawyers to figure out what he and so many of us seem to know instinctively.

“Probably another 15 years or so,” he said. “But it’s neither here nor there. The bottom line is, start to think about how manage, monetize, and measure information as an actual asset, and you’ll be playing really well into today’s information economy.”

Related Items:

Beyond the 3 Vs: Where Is Big Data Now?

‘What Is Big Data’ Question Finally Settled?