Fake News, AI, and the Search for Truth

(mstanley/Shutterstock)

Multiple weaknesses were exposed in public institutions in connection with last year’s election. First, cybercriminals tried to hack the outcome, then pollsters failed to read voter sentiment accurately. Finally, fake news crept into our news feeds, distorting our collective view of the real world. Can big data technology and artificial intelligence put us back on the straight and narrow?

We’ll soon get to find out. Following the election, Facebook revealed that it’s exploring ways that artificial intelligence can be used to prevent fake news from being distributed. The social media site has been criticized for not doing enough to stop users from circulating phony news stories that may have helped swing the election in favor of President-elect Donald Trump, an accusation the company vehemently denies.

Following the election, Yann LeCun, Facebook’s director of AI research, told a group of journalists gathered at its Menlo Park, California headquarters that an AI-based filter to detect fake news either already exists or could be built, according to a story in the Wall Street Journal. “Tens of employees” have been pulled off other projects to work on the fake news problem, the story says.

Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg outlined several steps the company is looking at taking to tamp down on fake news, including advanced technology, a user reporting system, a third-party verification system, and disrupting fake news “economies,” among others.

But better fake-news detection algorithms are at the top of the list. “The most important thing we can do is improve our ability to classify misinformation,” Zuckerberg wrote in a blog post. “This means better technical systems to detect what people will flag as false before they do it themselves.”

AI to the Rescue?

Big data technology could certainly help with detecting news stories. Bill Schmarzo, the Dell EMC vice president who’s been called the Dean of Big Data, says AI technology like machine learning and texting mining is perfectly suited for this type of activity.

“You can look through patterns and categorize and cluster the different articles that come up to see if there’s any sort of tendency going on,” he says. “You can come up with some kind of rating using the vast amounts of data coming out from these different sources, applying things like AI to understand the data and to create a credibility score that then, as a reader, I would have a hint that says I’m reading this story that comes from a [suspicious] site.”

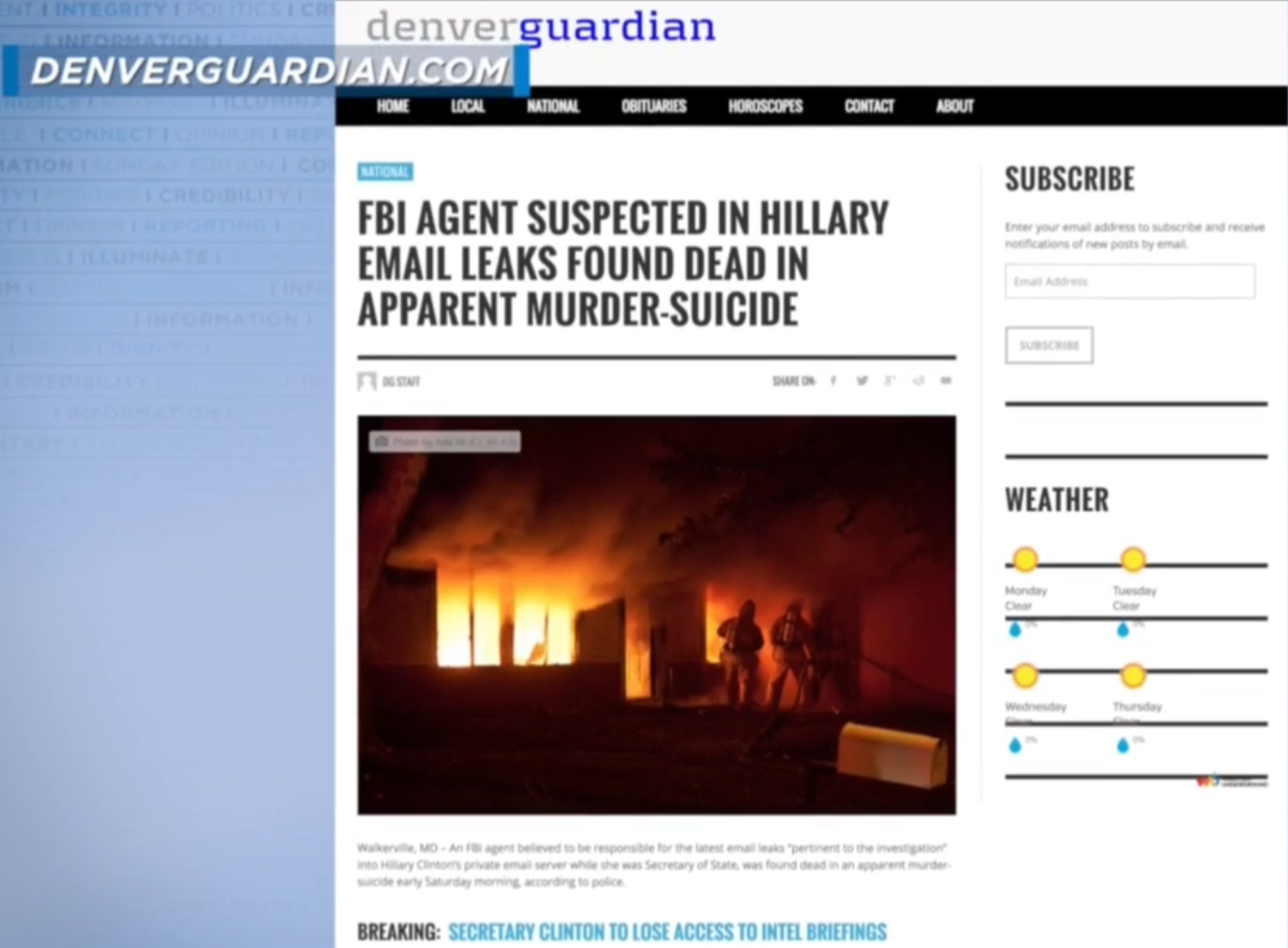

The Denver Guardian is a fake news site that published stories that appeared on Facebook

This sort of AI could help to prevent fake news—such as everything posted on the Denver Guardian (a fake news site) or a spoofed New York Times site that claimed Elizabeth Warren endorsed Bernie Sanders for president–from going viral.

“The technology is probably geared to more fast-moving news that’s spreading virally. This article is taking off fast. Flag it and throw it over to a human for review,” he says. “The technology is out there to help flag these things. But I still think there’s going to be a human component.”

It’s impossible to eliminate the underlying engine driving the fake news phenomenon (which isn’t necessarily a new phenomenon, and is sometimes called propaganda) because it’s inherently tied into human psychology, which makes any application of advanced technology a messy endeavor.

“Humans are really ineffective data processing and decision-making machines,” Schmarzo says. “What happens is they get an opinion in their mind, and then they search for data to support that decision. It’s called rationalization. It’s one of several decision-making flaws humans have.”

Hit It Like Spam

Seth Redmore, chief marketing officer at text analytics firm Lexalytics, agrees that AI technology can play a role in cracking down on fake news. But to really get a handle on the problem, it will require tacking it from multiple angles, he says.

(Kjpargeter/Shutterstock)

In addition to creating filters that detect and weed out fake news, users should consider creating white lists of reputable news sources. That will significantly reduce the odds of known fake news sources from spreading virally, he says. “It’s very easy to tell a machine that a news source is fake,” he says. The problem is people. “Even now, I still see once a month somebody mistaking an article from The Onion for being a serious article.”

We’re at a similar point with fake news today as we were with computer viruses and spam 20 years ago, he says. Eventually we’ll catch up, but it will take a bit of work. “We’re behind the curve, and we got really surprised by how powerful this was,” Redmore says. “There’s a bit of scrambling to catch up right now.”

Another approach to stopping the problem involves killing the funding. If brands like Proctor & Gamble or General Motors were aware that their ads were being displayed against fake news stories, they would immediately put an end to it, Schmarzo says.

“I would need to have a score to ensure that my brand marketers are having the right kind of experience on my social media network,” he says. “I’m dumfounded they didn’t do that. It seems like a pretty basic thing.”

‘Brain Viruses’

Redmore says blocking fake news, which he likens to “brain viruses,” will be a more difficult task than dealing with spam. For starters, spam followed a “push” delivery model that impacts individual email inboxes, whereas fake news has more of a “pull” delivery model where people are attracted to it because it aligns with their inherent biases.

(Joybakal/Shutterstock)

And let’s not forget that fake news, like it or not, is protected under the First Amendment to the US Constitution. Fake journalists enjoy freedom of speech, while legitimate news organizations scramble to avoid getting ensnared by the CAN-SPAM Act of 2003.

“My gut tells me fake news is going to be harder to classify [than spam] because it covers a broader range of topics and you can throw a lot more noise in there,” Redmore says. “Can we always determine what fake news is and always discredit it? We can’t do that with viruses, and that technology is hugely advanced.”

While AI technology could probably be developed that correctly identified the majority of fake news articles, the threat of false positives, or incorrectly labeling a real story as fake, is a major impediment to implementation.

Redmore uses the example of Sohaib Athar, the Pakistani IT professional who inadvertently live-tweeted the Navy SEAL raid that resulted in the death of Osama Bin-Laden in 2011. “When somebody finds something that is truly new and truly groundbreaking, it’s hard to filter it out from stuff that’s spam really,” he says.

This is the philosophical problem that Facebook is currently struggling with. In his blog post, Facebook’s Zuckerberg said the social media site doesn’t want to become the arbiter of truth. “We believe in giving people a voice, which means erring on the side of letting people share what they want whenever possible,” he wrote.

Truth in the Crosshairs

Even if you could train a machine learning algorithm with the entirety of human knowledge up to a given point in time, there would be no guarantee that it would not incorrectly flag a legitimate breaking news story as fake in the future. That’s because news, by its very nature, is adding to the corpus of human knowledge.

AI technology, for all its progress, still cannot accurately interpret the actual meanings of complex phrases; that capability is still five to 10 years away, Zuckerberg predicted last year. So to assume that an algorithm can correctly identify fake news means that it must be able to correctly determine whether a collection of words reflects the truth or not. That is a tall order in our complex world. In fact, it may never be accomplished.

Mark Zuckerberg says Facebook will err on the side of free expression when it comes to news (Frederic Legrand – COMEO/Shutterstock)

That’s not to say that progress can’t be made against fake news. As Schmarzo says, not all news stories have equal value, so one doesn’t need to boil the ocean by fighting every instance of fake news.

“One of the hard things that Facebook needs to look at is that stories that say Elvis Presley is still alive and working at a burger stop in Michigan. You know what? Who cares?” he says. “The cost of a false story on Elvis is zero. It’s immaterial, unless you own a burger place in Michigan.

“However, a false story about a presidential candidate or congressional nominee or police officer–these have a lot more weight to them,” he continues. “Those are really serious. You can leverage AI and text mining to flag those stories that are meaningful and have ramifications.”

And finally, consumers of news themselves need to be more critical of news stories themselves. They need to understand that, short of implementing draconian rules governing the distribution of information like they have in China, there’s no central source for “truth” on the Internet. It’s the Wild West out there.

People are free to explore information about anything they want, and are free to post anything they want, with a few exceptions. The role of the newspaper editor as your friendly neighborhood gatekeeper to pertinent information about your town and the world has basically been obliterated, replaced by Facebook feeds, Twitter posts, and Google News. There’s no way that AI can eliminate all instances of fake news on these sites, so some of the burden falls to readers to be more wary about what they read in their pursuit of becoming an informed citizen and voter.

Related Items:

AI to Surpass Human Perception in 5 to 10 Years, Zuckerberg Says

How Big Data Is Changing How Businesses Use The News