How AI Could Reshape Economies

(ktsdesign/Shutterstock)

As the field of artificial intelligence continues to expand, prominent scientists, business leaders, and politicians are expressing concerns about what this will mean for the future of work. Many conversations focus on the probability of robots taking away people’s jobs, but economies could be impacted in other ways. According to experts, AI technologies may also change the nature of work and affect financial services. Even if you keep your job, your day to day duties could be drastically altered by new AI-powered tools. Instead of probing these economic nuances, the news media has largely favored more apocalyptic interpretations.

Increasingly, doomsday forecasts are grabbing the most headlines. Elon Musk has characterized AI as “our biggest existential threat.” He recently tweeted, “If you’re not concerned about AI safety, you should be.” Stephen Hawking warned that “the development of full artificial intelligence could spell the end of the human race.”

AI concerns are not entirely unfounded. Employment has already been adversely affected by technological gains in automation. During an interview on David Axelrod’s podcast, Senator John McCain contradicted a central theme of President Trump’s campaign and administration. The senator stated that economic strife and middle-class devastation in the United States have been falsely attributed to foreign competition. “It has been technology that has caused these jobs to disappear a lot more than trade has,” explained McCain, highlighting the plight of “the auto worker that now watches an automobile put together by a robot, rather than an individual.”

McCain’s claims are supported by a report from Ball State University’s Center for Business and Economic Research. The study found that “almost 88 percent of job losses in manufacturing in recent years can be attributable to productivity growth,” as opposed to trade.

In his last interview as President, Obama echoed this sentiment and suggested that we need to be more creative when “anticipating about what’s coming down the pike.” He explained, “Automation is relentless and it’s going to accelerate.”

Elon Musk has compared AI investments to “summoning the demon”

An open letter from the Future of Life Institute notes, “There is now a broad consensus that AI research is progressing steadily, and that its impact on society is likely to increase.”

Full AI has not yet been realized, but the letter observes that there have been great strides forward in various component tasks. “The establishment of shared theoretical frameworks, combined with the availability of data and processing power, has yielded remarkable successes in various component tasks such as speech recognition, image classification, autonomous vehicles, machine translation, legged locomotion, and question-answering systems.”

Some industry experts estimate that we’re five to 10 years away from AI agents that will be able to manage an e-mail inbox on behalf of users. These AI assistants will act as an interface to knowledge and have been compared to executive assistants or personal coaches. Gmail unveiled a rudimentary form of this technology with the new Smart Reply feature. With the help of Smart Reply, users can quickly deal with incoming messages by selecting brief but relevant responses, generated entirely by machine learning.

Clever AI tools may initially bring peace of mind, but they’re also provoking fears about employment. E-mail management consumes a high percentage of many people’s workdays. If AI agents are perfected, many workers’ services could become redundant, either in whole or in part.

If AI does put people out of work, there may be a means of mitigating its impact. Bill Gates has openly suggested that we tax AI. By doing so, Gates believes that the excess labor can be used to reduce inequity, by transitioning a laid-off workforce to careers in social services.

“Right now, the human worker who does, say, $50,000 worth of work in a factory, that income is taxed and you get income tax, social security tax, all those things. If a robot comes in to do the same thing, you’d think that we’d tax the robot at a similar level,” stated Gates in an interview with Quartz.

Instead of viewing the redundant workforce as a negative, Gates views them as a freed-up resource that can be redeployed towards meaningful work, under the orchestration of government. He argues that uniquely human labor, and not AI, is required for work pertaining to the elderly, kids with special needs, and education because “all of those are things where human empathy and understanding are still very, very unique; and we still deal with an immense shortage.”

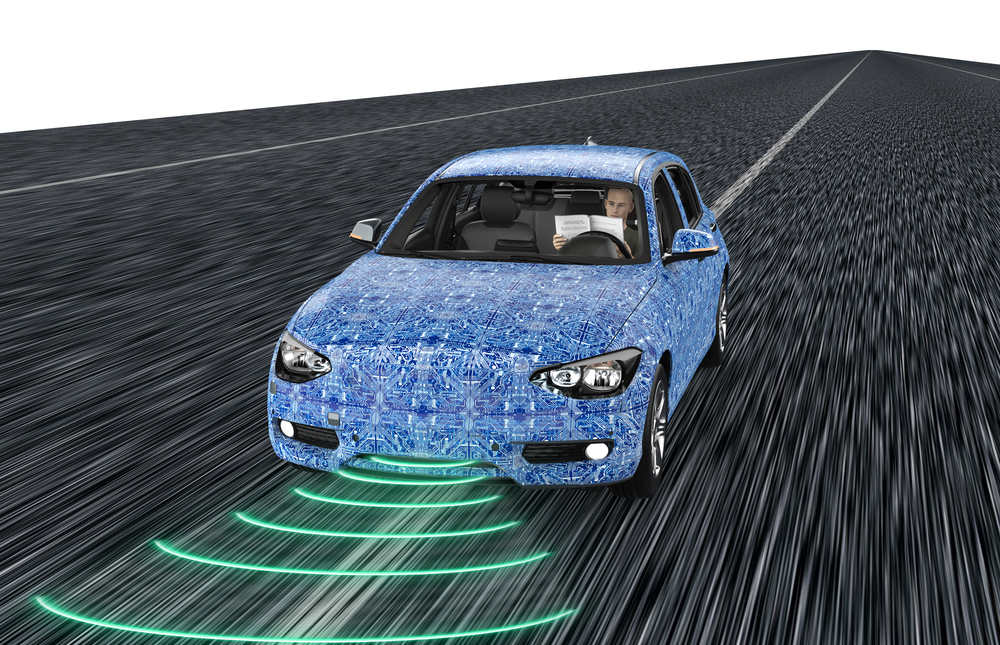

Transportation will be one of the first industries taken over by AI, experts predict

Stephen Hawking, like Gates, envisions a certain set of skills that are not easily supplanted by AI.

“The automation of factories has already decimated jobs in traditional manufacturing, and the rise of artificial intelligence is likely to extend this job destruction deep into the middle classes, with only the most caring, creative or supervisory roles remaining,” Hawking opines in a recent essay. He also emphasized the need for transitioning a laid-off workforce. “With not only jobs but entire industries disappearing, we must help people to retrain for a new world and support them financially while they do so.”

At the 2017 National Governors Association Summer Meeting, held in July, Elon Musk expressed his belief that human labor will eventually become inferior across all job sectors.

“There will certainly be a lot of job disruption. Because what’s going to happen is robots will be able to do everything better than us. I’m including, I mean all of us, you know,” he said.

Musk stated this prediction without equivocation, adding, “12% of jobs are transport. Transport will be one of the first things to go fully autonomous. But when I say everything, like the robots will be able to do everything. Bar nothing.”

At Google, François Chollet conducts research in deep learning, with a focus on computer vision and formal reasoning, such as automated theorem proving. He views AI as the latest wave of technological progress and points out that we have already automated activities in many other economic sectors.

“In 1850 the majority employment sector was agriculture, by a huge margin. In 1950 agriculture had become a minor economic sector, and a majority of jobs were in manufacturing. More recently jobs have shifted away from manufacturing,” Chollet explained, when interviewed for this article.

Chollet is mindful of the fact that technology has dramatically improved quality of life. He also sees the abundant opportunity.

“These waves of technological progress that are automating literally all the jobs are not actually reducing employment at all. Rather, they are shifting employment to new sectors, while increasing worker productivity across the board,” said Chollet.

Chollet described AI as the next evolutionary step of our society and a way to empower individuals. He said, “Unfortunately it’s much easier to predict which jobs will get automated than it is to imagine which jobs will be created, but that has always been the case. Pessimists have been warning everyone against technology-induced mass unemployment for over a hundred years. It has never come to pass.”

Richard Yonck, author of “Heart of the Machine: Our Future in a World of Artificial Emotional Intelligence,” believes that human damage is possible, due to the rapidity of our current technological era. He argues that sizeable job losses stemming from AI could cause people to reevaluate ideas such as universal basic income.

“While some of these solutions may go against many people’s personal politico-economic philosophies, the alternative damage caused by spiraling recession/depression should not be underestimated,” said Yonck.

Hedge funds are already using AI to predict market swings (ProStockStudio/Shutterstock)

Although these types of discussions are typically focused on the rate of employment, AI may have economic effects that extend well beyond the workforce. Numerous hedge funds are already using AI technologies to predict the performance of stocks and markets.

Aidyia, a financial tech startup in Hong Kong, was founded by computer scientists and financial market professionals. Its website states: “We deploy cutting edge artificial general intelligence (AGI) technology to identify patterns and predict price movements.” After conducting this analysis, their technology actually executes on trades with complete autonomy. The company assures investors that this innovative approach will provide them with “consistently superior returns.”

“The advantage will go to those who can really get and extract the insights of all the information we all talk about,” said Ginni Rometty, Chairman, President and Chief Executive Officer of IBM, while delivering her keynote speech at a banking conference. She hailed new advances in cognitive computing, which she described as “an era of systems that understand, they reason, and they learn. Just like the way you and I think.”

Rometty said that the financial sector will be at the forefront of AI. She explained, “It’s worth thinking back in time. It’s actually financial services that has led every other major area of technology. So, in all of mankind, there’s really only been two prior. There was a whole generation of things that counted, tabulated. Second generation was program, everything you have, your phone, you name it, is programmable today. It’s got to be told what to do. […] And this third generation is cognitive, things that will learn.”

“I don’t expect AI to have a huge impact on the market beyond what trading programs and high speed trading have already done,” said Richard S. Grossman, Professor of Economics at Wesleyan University and a Visiting Scholar at the Institute for Quantitative Social Science at Harvard University. “I think it is more likely that all the high-speed trading and various computer algorithms will lead people to place ever greater portions of their portfolios in index funds.”

Like Chollet, he noted that waves of technological innovation are a regular occurrence in the modern industrialized economy.

“Each new breakthrough brings with it benefits and costs: productivity and aggregate output increase, but some jobs disappear. Since we can’t outlaw technological progress—and probably don’t want to—we have to make sure that those who lose their jobs have access to the skills needed to participate in the resulting economy,” said Grossman.

About the author: David Pring-Mill is a writer and filmmaker. His nonfiction writing has appeared in The Los Angeles Times, The National Interest, openDemocracy, Independent Voter Network and many other publications. Follow him online: www.pring-mill.com, twitter.com/davesaidso.

Related Items:

Deep Learning Reveals New Insights About People

Putin: Who Controls AI “Will Be Ruler of the World”