Big Data and AI Converge in Map to Protect Biodiversity

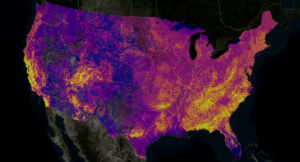

What’s living where? Those are the basic pieces of data that biologists and conservationists are hoping to collect and load into the Map of Biodiversity Importance, a dynamic new map unveiled this week at the Esri User Conference. And when mixed with other pieces of geospatial data and stirred with machine learning tech, the map will help conservationists predict the fates of thousands of endangered species.

The Map of Biodiversity Importance, or MOBI, is the result of the collective effort Esri, The Nature Conservancy, Microsoft, and NatureServe. The map, which was introduced onstage Monday at Esri UC but will make its public debut this fall, combines 2,600 detailed species habitat maps that have been collected over the past 50 years into a single searchable database that can be used by scientists and conservationists alike.

The Nature Conservancy has been working on biodiversity and conservation mapping for over 25 years, but most of the data has been very static, said Zach Ferdana, The Nature Conservancy’s geospatial information officer. MOBI helps to change that.

“Big data collection efforts that then become old and they’re done,” Ferdana said during a press conference yesterday at Esri UC. “This is revolutionarily in our ability to make a dynamic map, to update it, to add resilience and all the modules that we need to do in a very changing climate.”

MOBI lets scientists explore environmental conditions impacting endangered animals and plants around the U.S.

MOBI marks a significant upgrade from older methods scientists used to collect, aggregate, and analyst data from the field, NatureServe’s Chief Scientist Healy Hamilton said during the press conference.

“In the days before…we were mobile enabled in the field, we would have paper and somebody would go back and type it in,” Hamilton said. “And it would eventually go into a database and eventually somebody would pull from that database and do an analysis.”

But with MOBI, existing analyses can re-run and updated as soon as new data hits the database, she said. That’s a game-changer for scientists seeking synthesize better information and put it into the hands of conservationists to take action.

“It really is bringing together the technology, but putting it in the hands of people who are in the field and then creating that dynamic infrastructure so there’s almost no delay in how that information can update what we need for decision making,” she said.

In addition to simply mapping the location and volume of species found around the continental United States, MOBI will feature “predictor layers” that utilize machine learning and AI technology to make predictions on the species viability based on other variables, such as climate, soils, topography, and land cover, Hamilton said.

“Through machine learning, we can look at those predictor variables across a landscape and then project where else in the environment that combination of conditions occurs,” she said. “That’s what allows us to fill in the gaps, because we can’t survey for everything everywhere. It’s just not possible. That’s where we get our map, which is a hypothesis, testable by dynamic means, and citizen scientists who can also add to that data.”

Esri’s flagship product, ArcGIS, makes merging geospatial data a relatively easy process. But MOBI also includes open data science tools, including the Jupyter data science workbench, where users can bring in Python models to help them understand nuances of specific regions.

Together, the various pieces of technology combined in MOBI to enable geographical design, said Lucas Joppa, chief environmental officer at Microsoft.

“To do geo-design, you have to understand what is where, how much is there, and how fast it’s changing,” Joppa said during the press conference. “And if you ask that simple question of what is where, which is what the Map of Biodiversity Importance actually for the first time for some really important species — when you ask that question generally, you realize that we know very, very little about what needs to be done.”

What needs to be done, in the opinion of many at the Esri events yesterday, is more conservation. MOBI will directly impact that, said Sean O’Brian, the president and CEO of NatureServe. “This map is a roadmap to where people should buy land to protect threatened and endangered species,” O’Brian said.

Also speaking to the press at Esri UC was renowned naturalist Jane Goodall, whose pioneering work with chimpanzees starting in 1960 helped galvanize conservation efforts in Africa. Goodall now spends 300 days a year travelling and spreading the word of the need to conserve natural resources.

“If you don’t protect the habitat, you can’t protect the creatures,” Goodall said during a press conference. “By protecting the forest, we’re protecting the biodiversity of the forest. Without the biodiversity, the forest won’t survive. So it all ties in together. It’s all inter-related.”

Goodall spoke alongside Jack Dangermond, the president and founder of Esri, and EO Wilson, an American biologist. Dangermond, who studied landscape engineering at Cal Poly Pomona before creating the precursor to ArcGIS at Harvard University in 1969, became one of the foremost conservationists of his generation in 2017 when he and his wife, Laura, gave $168 million to the Nature Conservancy to protect a 24,000 acre parcel of land on the Pacific Coast near Santa Barbara.

Esri founder and president Jack Dangermond (left) discusses conservation with primatalogist Jane Goodall (center) and biologist E.O. Wilson (right) July 9 in San Diego, CA

MOBI is a direct result of the effort to save that largely unspoiled stretch of land, formerly called Bixby Ranch, where the Dangermond’s honeymooned after they got married, according to this National Geographic story. “A few weeks before it was announced publicly in December 2017, Jack gave us a call and said I want that map for the nation where other people can know where to invest,” NatureServe’s Hamilton said. “Friends of his will know where to protect the most endangered species.”

We’re moving into an age where virtually everything that moves and changes will be measured, said Dangermond, who sounded optimistic that we can use this data to better understand “the nervous system of the planet.”

“Following understanding, we can then carry out intelligent actions,” Dangermond said. “The designers of the world – engineers, planners, all types of people who affect the planet, even farmers — they need to learn how to design proactively to create the future. You learn how to design using geographic knowledge as a foundation.”

If we truly understood our footprints, we would change our behavior, he added. “But we’re still arguing what’s on the right, what’s on the left…..[We’re] talking about political BS rather than focusing on what needs to be done, which is creating a science foundation for all of us to create a better future.”

Related Items:

Big Bird Data Project Probes Migrations

Esri Adds an Unstructured Location Data Capability

For Esri, Analytics All About Location, Location, Location