Coming to Grips with COVID-19’s Data Quality Challenges

(OSORIOartist/Shutterstock)

The COVID-19 pandemic is generating enormous amounts of data. Large amounts of data about infection rates, hospital admissions, and deaths per 100,000 are available with just a few button clicks. However, despite the large amount of data, we don’t necessarily have a better view of what’s actually happening on the ground, and the big COVID-19 data sets aren’t directly translating into better decision-making, data experts tell Datanami.

As we’ve discussed many times in this publication, managing big data is hard. It’s not difficult to store petabytes worth of data (or even exabytes, which is fast becoming the delineation point for “big data”). But if you want to store that data in a manner that allows groups of individuals to access, analyze, and use that data for modeling purposes in a clean, repeatable, secure, and governed manner – well, that’s where things get interesting.

The COVID-19 pandemic is a once-in-a-lifetime event (hopefully) and organizations around the world are pulling out the stops to get in front of the disease. That has triggered a veritable tsunami of data collection and generation.

Unfortunately, in the heat of the viral emergency, organizations haven’t put as much thought into important details about the data, ranging from how it was collected and transformed, what format it’s stored in, who has access to it, and how accurate it is. That’s to be expected during a time like this, but it doesn’t help the situation.

COVID-19 Data Chaos

When Fraser Marlow and Thomas Bennett of Talend started seeing all the COVID-19 data silos popping up, it immediately reminded them of the data management challenges they’ve helped many corporations overcome.

“When this crisis started to break out, we looked at each other and said ‘This is what we do. This is what Talend does,’” Bennet says. “We give you access to the data. We can help with the quality, the curation, of it, and provide it to you in a deterministic format that you can then take and make those decisions on. Given the lack, therefore, of a standard format, we said, let’s put one together, because this is what we do for a living.”

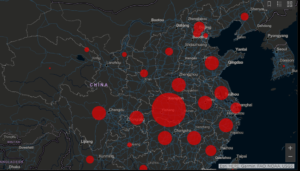

The COVID-19 dashboard from Johns Hopkins University has become a go-to source for data about the outbreak

Talend’s curated COVID-19 data library is composed of data sourced from Johns Hopkins, the EU, Italy Data, the New York Times, Neher Lab Scenarios Data, and the COVID-19 Tracking Project. These data sets all have good underlying data, but that doesn’t’ mean they don’t’ have issues, Marlow says.

“I’m sure you’ve heard of the Johns Hopkins data set, which has become somewhat canonical at this point. Everybody is referring to it and it is very high quality,” Marlow says. “But of course they’re getting their data from somewhere. And the people they’re getting the data from, they’re getting the data from somewhere.

“What we realized was every research group was trying to unravel this ball of string, because not only were data sets pulling from other data sets, but often they were cross-referencing, de-duplicating, often adding data,” he continues. “You’re left with real problems with data quality, data integration, data governance. We saw the same thing emerging around the COVID data sets popping up.”

The quality problems that Talend found in the COVID-19 datasets will sound familiar to corporate data engineers. States and cities were grouped in the same field, and dates were not represented consistently. In some cases, each iteration of time-series data–such as the daily count of positive coronavirus tests–was represented in separate columns, which isn’t ideal for analysis in a column-oriented analysis (as most modern analytical databases use).

So far, more than 40 organizations around the country have used the Talend COVID-19 dataset, including local healthcare authorities. It’s been worthwhile to see the impact that the refined and reliable dataset is having on decision-makers, Bennet says.

“It was complete chaos of how to mash it all together, how to tie it all together,” he says. “That was the worst part. I can only imagine a data scientist or data engineer trying to pull this together and create something with it and have people wonder ‘What does this column mean versus this column.’”

COVID-19 Data Quality

With so much data flying around that’s of questionable quality, decision-makers should approach the data carefully, says Chris Moore, director of solution engineering at Trifacta.

Many of the problems around enterprise data quality are present with COVID-19 data (via Shutterstock)

“It’s been great to see the growing number of datasets that have been made available for COVID research and response efforts,” Moore says. “Unfortunately, a lot of this data has questionable quality and underlying structural issues. It’s also critical to have a solid understanding around the context of the data – how it was assembled, metadata around each feature, when it was last updated, etc.”

It’s especially important to investigate the data’s quality if it’s going to be used for machine learning purposes, Moore says.

“Decision-makers should make sure that they understand the context of the data they’re using before they can confidently make decisions off of it,” Moore tells Datanami via email. “I also recommend that people try to compare datasets provided by different outlets. If there’s a dataset that shows trends that massively differ from multiple others that contain similar information then it might put into question the validity of that dataset.”

Data Transparency

With so much COVID-19 data flying around, it’s best to take the data with a grain of salt, especially at this stage of the crisis, says Matt Holzapfel, solutions lead at Tamr.

“I think there are enough sources of data to see the ranges of predictions and use those ranges in order to establish some level of confidence in what the range should be,” he says. “I think trying to use the data to come up with absolute claims is a wasted exercise.”

Skeptical data consumers could learn from enterprise in how they approach new data sets, Holzapfel says. In that respect, COVID-19 data is no different than any other piece of data that an enterprise is used to dealing with, he says.

“If someone gives you a data set, one of your first questions is where did you get it from and what did you do to it,” he says. “I think we need much more transparency with regard to this [COVID-19] data to understand it. If people are taking out things that they consider outliers, we should know that, because the raw data is very powerful.”

Without transparency around the data, users run into the danger of assuming a given piece of data is of higher quality than it really is, he says.

“There’s the risk of everything being pulled from the same source and everyone is doing their own transformation on the data and we have no visibility into that,” he says. “What I’d like to see is data providers who are doing those transformations being transparent about it.”

A COVID-19 Data Catalog?

Before making a decision, it’s important to get a wide view of all of the relevant data sources. That is the essence of being “data-driven,” after all. But that’s a challenge in the current COVID-19 situation, because there are so many disparate data sets popping up everywhere, says Dr. Pragyansmita Nayak, chief data scientist at Hitachi Vantara Federal.

“Before you can even say your data is accurate, are we looking at all the data sources?” she asks. “When you talk of data sources, think of them as assets. They can be different avenues of information that’s happening. And having a central location where you have visibility into these different data assets and being able to get more of a holistic look into it.”

Ideally, public health officials would not only have a standardized format for handling outbreak data, but they would also have a centralized data catalog that stores metadata about all the various data sets. According to Nayak, it wouldn’t be necessary to have all the data in one place, if access can be federated via a catalog, she says.

The Federal Government has been working to share data for several years through its Data.Gov initiative, she says. But it’s too late to build higher order products, such as a data catalog for infectious diseases data in general or a COVID-19 catalog specifically, at this point in time.

“This is something that you have to plan for,” she says. “It’s kind of a rude awakening that these types of data catalogs and stuff like that – it should have been in place before. It’s not something you put in when you’re on fire, for sure.”

Related Items:

Data Transparency: Lessons from COVID-19

A Race Against Time to Model COVID-19